Interventions with companion animals are an everyday occurrence to so many people and occur in a huge variety of settings. When these interactions are positive, it can be very rewarding for both the humans and animals involved; but when things don’t go right the consequences can be devastating.

The 2019 SCAS conference focused on the One Welfare aspects of our relationship with companion animals, including situations where such interactions are not good for those involved. The One Welfare concept serves to highlight the interconnections between animal welfare, human wellbeing and the environment.

“It’s essential to discuss the balance when it comes to our interactions with companion animals,” said Dr Elizabeth Ormerod, chair of the SCAS board. “While so many of our day-to-day activities with our pets bring enormous benefits, we have to recognise that not all situations are so positive; either for the person, the animal or both.”

The Society for Companion Animal Studies (SCAS) is a charity that works to offer scientific evidence of the benefits that animal-human interactions can bring and positively promotes the benefits of pet ownership (under appropriate welfare conditions); it was these themes that were explored during the conference.

The Board was delighted that Chris Lawrence agreed to be conference chair, bringing his boundless knowledge and experience to present a coherent and considered view of the One Welfare concept in the context of companion animal ownership to an enthusiastic and interactive audience.

Dr Ormerod, who has been actively involved with SCAS for over 30 years, presented a review of the incredible body of work that has been produced, underpinning the science behind the human-animal bond (HAB). “This field has come such a long way in the 40 years that SCAS has existed. The evidence base has grown and we understand so much more about the relationship between companion animals and humans and how we can strive to make it a positive experience.”

Captivating speaker, Dr Anne McBride, presented a broad picture of situations where human-animal interactions deserve closer examination due to the potential of compromised welfare of animals – and sometimes the potential for impaired human welfare. Dr McBride explored the role of keeping a companion animal and how it is a functional role, for the benefit of the human, and that it does not necessarily confer any emotional attachment from the human.

The role of the companion animal can take myriad forms, from a commercial role (such as a racing greyhound), a show animal, or kept for protection or companionship. She explained how the label of the companion animal can change and, once it does, the role and status of the animal instantly changes with the new label given.

Using dogs as an example, a “street dog” may be considered a pest, but if it is caught and rehomed it is considered a “rescue dog” and therefore a companion label is given. The status of the dog may change again if the animal is given away or has behavioural issues, and it may end up being euthanised or passed on elsewhere, again changing its “label” and status.

Another example involved the feeding of rabbits to snakes, with one owner describing how they bred and raised “meat rabbits” to feed live to their “pet” snake and making a distinction between these to say that they are “not pet rabbits but meat rabbits…”. This is an example of how labels can confer a certain status to an animal when denoted by humans.

Extending the example of dogs, Dr McBride described how humans have made companion animals fit with their own lifestyle, whether or not it suits the animal – for example conferring certain behaviour traits, such as to not jump up at people and leaving a dog on its own for the most of the day. This also applies to aesthetics, she said, which manifests itself through the selective breeding of certain traits, one being brachycephalism, purely for the gratification of humans but to the detriment of the companion animal.

Dr McBride then raised the question of what can be done about it. The problem lies with us, as humans and acknowledging this is the first step to addressing the issues, she said. Licencing of animal ownership and introducing higher associated costs could work, but there are many factors contra-indicating this; “If it hits people’s pockets it may help influence behaviour change,” she said.

But many of the benefits of pet ownership are not monetary and this is where the biggest challenge lies. People find many companion animals “just so cute” and the perception is that they are “so good for me” that the welfare implications for the companion animal are bypassed. One situation where this is witnessed is with some emotional support animals, where the need of the human is considered of paramount importance, thus eclipsing the animal’s own needs.

“We need to move from a model of enforcement to enforcement plus education. To move towards understanding the needs of all involved and evolve better communication across the spectrum – from suppliers to consumers and encourage cooperation at all levels of the industry,” she added.

The One Welfare concept is important to strive for, but it will involve human behavioural change. Much more research is required, she suggested, emphasising how this must be multi-disciplinary. “We need to understand how humans work to be able to influence them,” she concluded.

Renowned speaker on exotic species, Clifford Warwick, presented delegates with a view of the extensive scale of morbidity and mortality arising from the pet trade in exotic species across the world. The keeping of exotic species has long been the subject of debate and the suitability of these species as pets has been brought into question on many levels, including welfare, zoonoses and the environmental and ecological impact of removing swathes of animals from their wild habitats and spreading them around the world where they have the potential to establish as invasive species. Clifford Warwick explored both of the routes in which exotic animals will come to market: through capture direct from the wild and via captive breeding.

The death rates of exotic animals imported as pets can only be described as terrifying, let alone the welfare issues that arise from husbandry after purchase of these animals. His statistics showed the following:

- animals in general = 70% general mortality in 6 weeks industry standard at pet suppliers;

- marine fishes = 98% capture mortality; and

- reptiles = 75% mortality within 1 year in the home.

Ownership of exotic pets touches all aspects of the One Welfare concept and is brought into sharp focus through the huge numbers of animals being taken from the wild, decimating populations, as well as the welfare issues around export and subsequent husbandry for the specimens that do survive to become owned “pets”.

He explained the main welfare issues arise due to ignorance around the needs of exotic species, focusing in on how they are deprived of natural living conditions. This includes the following:

- Spatial

- Thermal

- Exercise

- Behavioural

- Psychological/mental

- Sociality

- Environmental cues

- Chemical cues

- And others…

The needs of exotic species are difficult to meet; this is where one of the most significant problems arises with their care. Marketing around the keeping of exotic animals as pets promotes them as “easy to keep” and “low maintenance” which totally counters the reality of keeping exotic species healthy and in anything like natural conditions.

This issue is coupled with the fact that there are over 13,000 exotic species kept as “pets” and therefore the knowledge required for their care is just not known or available. “Caring for a baby is one species, cats and dogs just two species, caring for exotic animals involves 13,000 species; how can we possibly monitor this?” he stated.

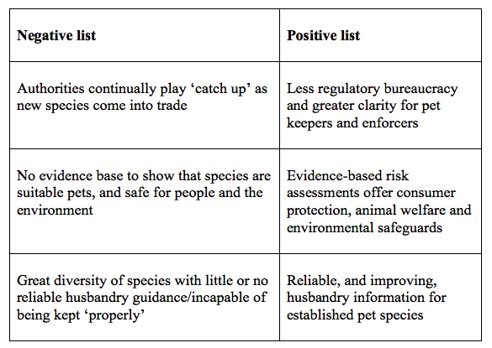

There are no easy options for confronting the One Welfare issues around the keeping of exotic animals as pets. Clifford Warwick described various approaches to be considered. These included more explicit labelling of pets, instigating suitability tools (for example the Easy, Moderate, Difficult, Extreme [EMODE] tool), education and the introduction of “positive lists” that name a few exotic species deemed more suitable for keeping in homes. Both bans and positive lists have been effective where introduced for target species, he suggested.

“During the 1950s-1990’s terrapins were imported into the UK at rates around 200,000 animals annually, and into Europe 7 million annually. Since the ban in 1997 the trade has diminished to almost zero.”

In the USA, around 14 million terrapins were imported annually, but since the ban the trade has diminished to near zero – there has also been a 77% reduction in salmonellosis associated with reptile contact.

Table 1. A comparison of the effects of negative vs positive ownership lists for exotic species.

The morning also including two other fascinating talks; one by Debbie Rook on Pets and Housing and another by Vicki Betton on Domestic Pets.

Not everything on the day was lecture-based, the afternoon session was split into three different workshop (housing, domestic pets and exotic pets) groups so practical ideas could be discussed. These workshops gave us some actions to take forward in the future.

Delegate feedback was overwhelmingly positive with 95% of delegates saying they were satisfied or very satisfied with the conference!

We would like to thank everyone who came along – delegates, speakers and exhibitors for making the conference such a success.

Poster Competition

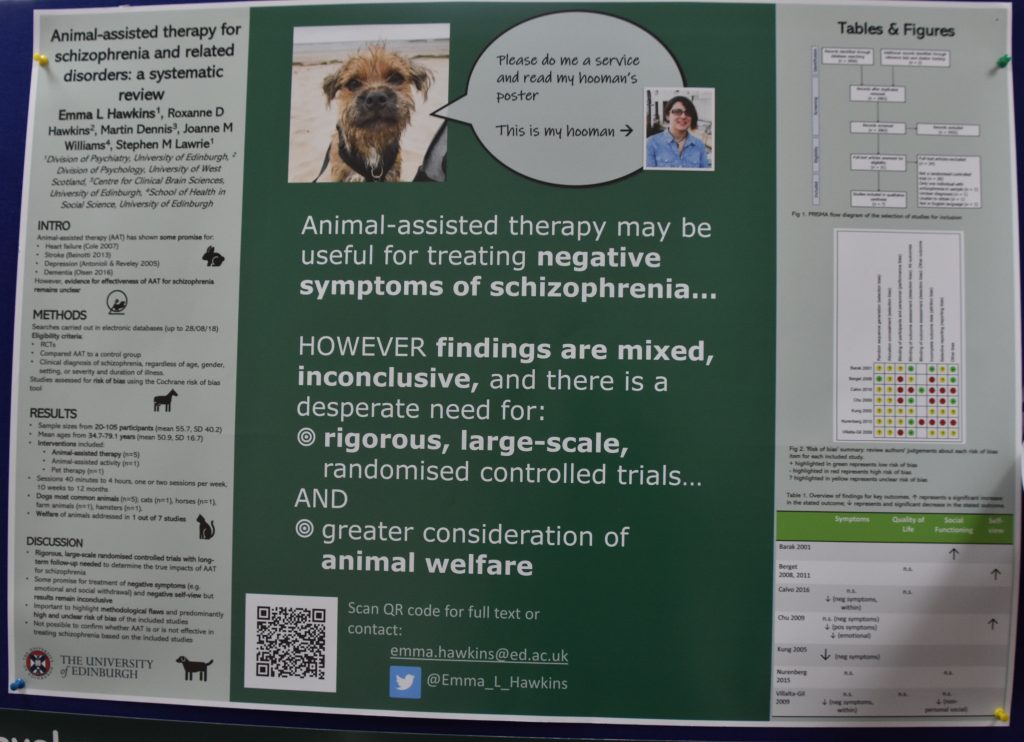

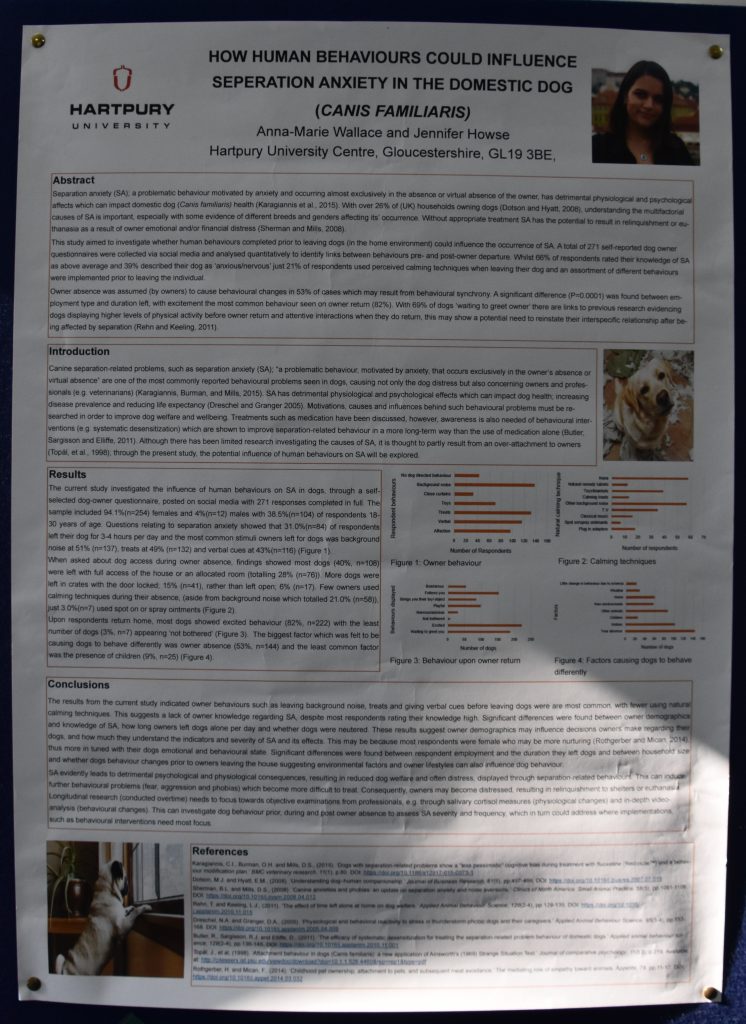

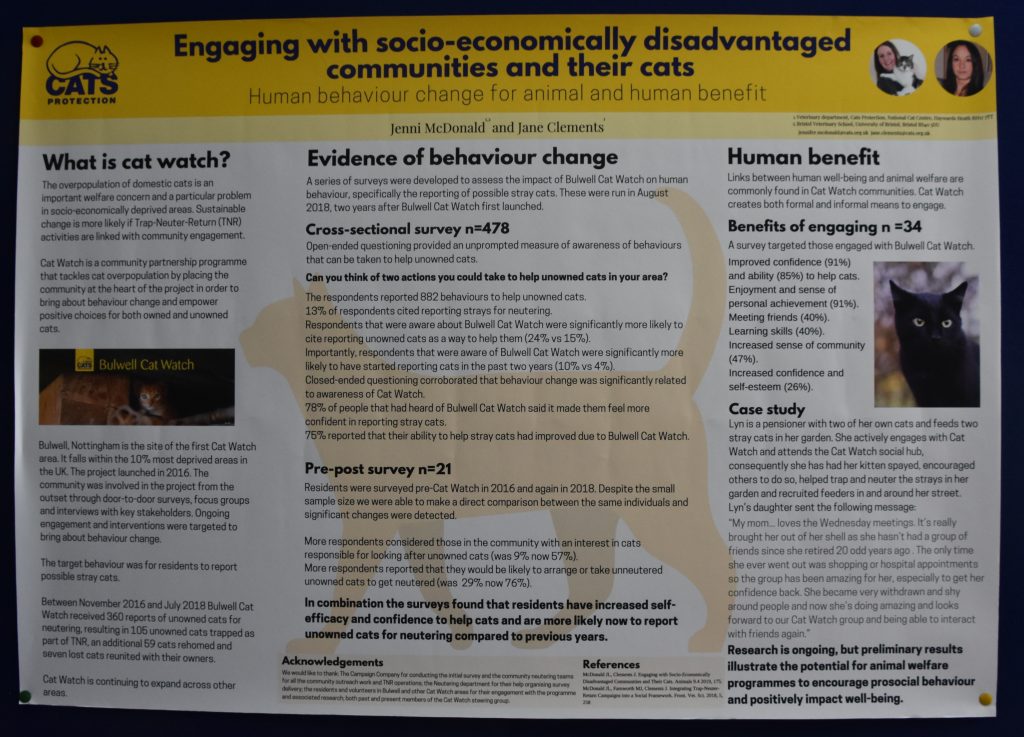

Congratulations to Sarah Gordon for winning the conference poster competition, and to Jennifer McDonald and Jane Clements for being runners up. A big thank you is extended to everyone who submitted a poster – they really were excellent and thought provoking. A selection can be seen below:

Sarah Gordon – Paws: Animal Assisted Therapy C.I.C

Jennifer McDonald and Jane Clements – Cats Protection